Thursday, October 15, 2009

School

A call for students. Sierra Leonean kids want to communicate but don’t have computer access. If you would like to chat with a student in the City of Bo, Sierra Leone let me know at pjfishing@yahoo.com and I’ll hook you up through Local Government officer Sheka Kamara.

Like all parents the world over, education in Sierra Leone is highly valued and great sacrifices are made by many for the future generation. The enlightened see education especially of girls as the way out of poverty. However the education system has badly failed due mainly to the lack of teaching skills and poor treatment of teachers.

Non Governmental Aid seems to have focused on the construction of buildings rather than to increase the capacity of local government to provide the teaching materials and the central Government to provide sufficient salaries.

Non Governmental Aid seems to have focused on the construction of buildings rather than to increase the capacity of local government to provide the teaching materials and the central Government to provide sufficient salaries.  Meanwhile The World Bank complains in a recent report that “Sierra Leone needs to show clear evidence of the effective use of funds already available, together with a credible plan for utilizing future, additional resources” Obviously funds are provided but are not being used – sadly we should read corruption, an all too common thread.

Meanwhile The World Bank complains in a recent report that “Sierra Leone needs to show clear evidence of the effective use of funds already available, together with a credible plan for utilizing future, additional resources” Obviously funds are provided but are not being used – sadly we should read corruption, an all too common thread.Officially school fees are abolished for 6 primary years and for a further 3 years for girls. Nonetheless 25% of children don’t attend especially among the poorest.

Moreover the standard of schooling is dreadful. Schools in Sierra Leone are considered as “public” since they are funded out of the central government budget (funded almost 50% each year by the World Bank). The funds are then trickled to Local Government such as Bo and Makeni to maintain and build the buildings, supply school materials and implement curriculum.

Moreover the standard of schooling is dreadful. Schools in Sierra Leone are considered as “public” since they are funded out of the central government budget (funded almost 50% each year by the World Bank). The funds are then trickled to Local Government such as Bo and Makeni to maintain and build the buildings, supply school materials and implement curriculum.  The teachers are paid by Central Government – a tiny amount of about $40 per month for first year graduates although this is frequently late and occasionally not paid at all.

The teachers are paid by Central Government – a tiny amount of about $40 per month for first year graduates although this is frequently late and occasionally not paid at all.  Notwithstanding this I am astounded that many students wish to be teachers – mainly because there are so few other alternatives. I now know that the teachers survive by accumulating money or benefit from the parents and children in various ways. The children are “taught” farming by doing it on school grounds and the resulting crops are then appropriated by the teacher. Teacher brings home cooked treats to class and the children are expected to buy. Marking papers, photocopying texts and an array of methods

Notwithstanding this I am astounded that many students wish to be teachers – mainly because there are so few other alternatives. I now know that the teachers survive by accumulating money or benefit from the parents and children in various ways. The children are “taught” farming by doing it on school grounds and the resulting crops are then appropriated by the teacher. Teacher brings home cooked treats to class and the children are expected to buy. Marking papers, photocopying texts and an array of methods  supplements the income.

supplements the income. Importantly education is supposed to be “free” for those in primary school - under 12’s but in reality it’s quite different, largely because the teachers are not paid enough.

Importantly education is supposed to be “free” for those in primary school - under 12’s but in reality it’s quite different, largely because the teachers are not paid enough.The other big problem is that the standard of education is so poor, the main issue being the poor training standards coupled with the poor pay. Public schools seem to spend a high proportion of the year doing non teaching such as a sports week and a farming week.

All these issues are accentuated by the huge class sizes that can reach over 100 kids crammed into an often dark and dismal room seated on rough wooden benches. The World Bank reports that “Most schools in Sierra Leone have very poor classroom conditions and still lack sufficient learning materials and adequately qualified teachers; learning in many schools

All these issues are accentuated by the huge class sizes that can reach over 100 kids crammed into an often dark and dismal room seated on rough wooden benches. The World Bank reports that “Most schools in Sierra Leone have very poor classroom conditions and still lack sufficient learning materials and adequately qualified teachers; learning in many schoolsis minimal.“ A sad indictment, but obvious when seen just casually on the ground.

The dismal standard is recognized by parents most often seeking private schools if they can afford it. Private schools are quite common and are usually built on a religious foundation.

I visited one school run by a Bo City Councilor Abdul Karim Sesay.

I visited one school run by a Bo City Councilor Abdul Karim Sesay.  Sesay who is a fully qualified teacher and was a public school principal is also the Chairman of the property tax and licences committee. I often had to interact with Sesay but we didn’t always agree.

Sesay who is a fully qualified teacher and was a public school principal is also the Chairman of the property tax and licences committee. I often had to interact with Sesay but we didn’t always agree.  Recognising the problems in the publicly funded schools Sesay started his own primary school only last year with a series of other teachers and I went to visit.

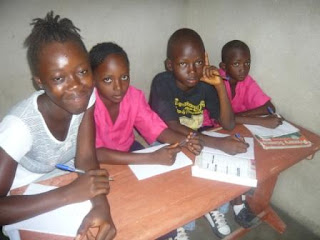

Recognising the problems in the publicly funded schools Sesay started his own primary school only last year with a series of other teachers and I went to visit.  The school is located in a poorer residential area and is an old mud brick house with 5 rooms. Mindful of the parents lack of discretionary cash, students don’t have to wear a uniform. Islam is the foundation of the school and there is religious instruction. However it is obvious that Christian students also attend.

The school is located in a poorer residential area and is an old mud brick house with 5 rooms. Mindful of the parents lack of discretionary cash, students don’t have to wear a uniform. Islam is the foundation of the school and there is religious instruction. However it is obvious that Christian students also attend.  Prayers are said for both religions and I’d say that 25% of the kids are Christian. The school is cramped and 4 of the rooms are dark.

Prayers are said for both religions and I’d say that 25% of the kids are Christian. The school is cramped and 4 of the rooms are dark. However there are about 200 students already. Costs are under $20 per year and there is considerable leniency for some parents.

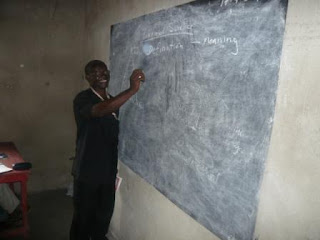

However there are about 200 students already. Costs are under $20 per year and there is considerable leniency for some parents.  Things like paper and pencils are extra. Books – well there are none. Instruction comes from the chalk board and the students seem to copy from the board or by rote from the teacher. The important element here for Sesay is that the class size is smaller and although the teachers are not well paid at the moment, they are more dedicated than his experience as a Principal in the public school.

Things like paper and pencils are extra. Books – well there are none. Instruction comes from the chalk board and the students seem to copy from the board or by rote from the teacher. The important element here for Sesay is that the class size is smaller and although the teachers are not well paid at the moment, they are more dedicated than his experience as a Principal in the public school.  The plan is that when the school becomes more popular then better funding will be available. The teachers appear to be prepared to wait.

The plan is that when the school becomes more popular then better funding will be available. The teachers appear to be prepared to wait. Interestingly the name of Sesay’s school is Al Gaddafi Comprehensive Academy and honours the Libyan leader, somewhat strange since Gaddafi was known to have financed the rebels during the war in Sierra Leone (for obvious diamond access). Sesay explains that Gaddafi has recently been very generous for Sierra Leone. I am constantly surprised at how easy it is to buy favours, even a foreign despot like Gaddafi.

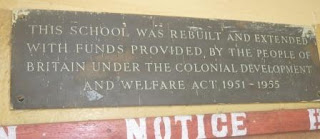

Interestingly the name of Sesay’s school is Al Gaddafi Comprehensive Academy and honours the Libyan leader, somewhat strange since Gaddafi was known to have financed the rebels during the war in Sierra Leone (for obvious diamond access). Sesay explains that Gaddafi has recently been very generous for Sierra Leone. I am constantly surprised at how easy it is to buy favours, even a foreign despot like Gaddafi.At the other end of the scale is the very privileged Bo School founded by the British in 1906.

Of course this is for boys only.

Of course this is for boys only.  Many of the most influential politicians and the successful in the country were educated here and

Many of the most influential politicians and the successful in the country were educated here and  competition for entry is enormous. Apart from fees the family has to be well connected. Whilst in Bo I lived opposite the school grounds and used the football pitch for morning exercise.

competition for entry is enormous. Apart from fees the family has to be well connected. Whilst in Bo I lived opposite the school grounds and used the football pitch for morning exercise.  The model is obviously based on the English Public School and the construction was funded by the UK in the early 1950’s. Funding for the school is very poor and there is no longer any support from the former imperious “British Colonial Office”.

The model is obviously based on the English Public School and the construction was funded by the UK in the early 1950’s. Funding for the school is very poor and there is no longer any support from the former imperious “British Colonial Office”.  The impression, just looking at the grounds is one of sad neglect; likely no maintenance for over 50 years. Buildings now are sadly in a poor and dilapidated condition. Nonetheless this is the best there is.

The impression, just looking at the grounds is one of sad neglect; likely no maintenance for over 50 years. Buildings now are sadly in a poor and dilapidated condition. Nonetheless this is the best there is.Dormitories house about 400 boys and there are another 400 day boarders. Students who are typically Mende have an air of superiority much like at English public boarding schools and they seem very polite and well mannered.

A discussion in the early morning reveals very lofty ambitions of high Government office, banking or an education in the US but few wanted to go into industry. (Unlike Makeni none of the boys joined me in an early morning jog)

A discussion in the early morning reveals very lofty ambitions of high Government office, banking or an education in the US but few wanted to go into industry. (Unlike Makeni none of the boys joined me in an early morning jog) I noted on the notice board recently that the Principal Bob Katta

complained bitterly about the poor performance with only two students passing the regional examinations

complained bitterly about the poor performance with only two students passing the regional examinations  WASSCE this year.

WASSCE this year.  I met Mr Katta one morning after a jog and I asked him about the challenges of getting

I met Mr Katta one morning after a jog and I asked him about the challenges of getting  students through the regional exams and he squarely pointed to the falling standard of teaching as a result of the war.

students through the regional exams and he squarely pointed to the falling standard of teaching as a result of the war.  He is hoping for improvement but it is going to take much to recover.

He is hoping for improvement but it is going to take much to recover.Altogether this is a rather sad story and it is easy to feel hopeless. I feel that with locally driven funds this will lead to better responsibility and to better teaching conditions.

Aid as it is now provided is simply abused and leads easily to corruption thereby hindering progress.

Aid as it is now provided is simply abused and leads easily to corruption thereby hindering progress.  It is easy to voice a call for no aid but unless education is tackled, people stay dreadfully poor and the youth succumb to rebelliousness and fanaticism.

It is easy to voice a call for no aid but unless education is tackled, people stay dreadfully poor and the youth succumb to rebelliousness and fanaticism. Somehow intelligent people in the worlds development industry need urgently to come together, co-ordinate and help mobilise some change. Local people seem to know what they need and want but they urgently need some intelligent guidance.

Somehow intelligent people in the worlds development industry need urgently to come together, co-ordinate and help mobilise some change. Local people seem to know what they need and want but they urgently need some intelligent guidance.